The dramatic fall in share prices over the past few weeks has generated much media coverage and uncertainty around of the effects of the coronavirus on individuals, supply chains and the broader economy. This is understandable, given the rapid fall in shares of around 15%, but let’s put things into perspective.

We are of the view that this event is just another correction, although share prices may still have more downside.

What is driving this correction?

- After strong gains in share markets, and in some cases over-valuation of asset prices, they have become vulnerable to a correction.

- Uncertainty of the effect on health systems and supply chains outside of China, including northern Italy, South Korea and Iran, resulting in a longer and deeper hit to global growth.

The volatility index (VIX) and market resilience indicator (which hit a record 54.4 – its highest since January 2009 – before settling to 40), is very elevated, suggesting we are not yet near the bottom of this correction.

Considerations for investors

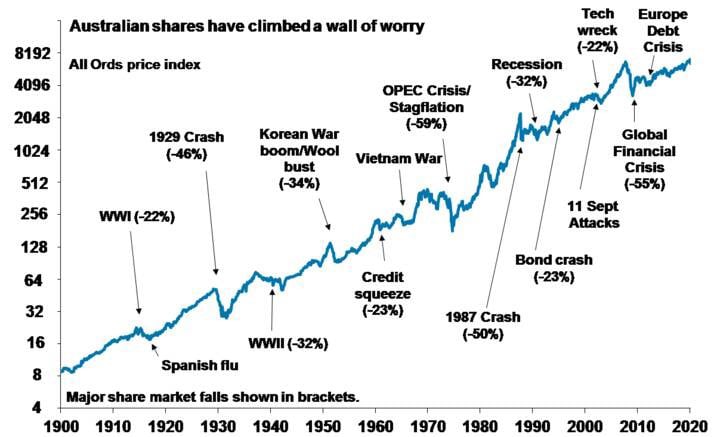

First, while corrections all have different triggers and unfold a bit differently to each other, periodic corrections in share markets of 5%, 15% or 20% are normal and healthy. For example, during the tech/dot-com bubble that commenced in 1995 and burst in 2001, there were seven downturns greater than 5%, ranging from 6% to 19%. During the same time, Australia had eight downturns of similar range. In the bull market from 2003 to 2007, the Australian share market had five corrections ranging from 7 to 12% and, more recently, a 20% fall between April 2015 and February 2016 and 14% fall from August to December 2018.

Share markets are resilient and can withstand periods of concern, over the long-term, and ultimately trend up, providing higher returns compared to other stable assets. Bouts of volatility are the price we pay for the longer-term returns from shares.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

Source: ASX, AMP Capital

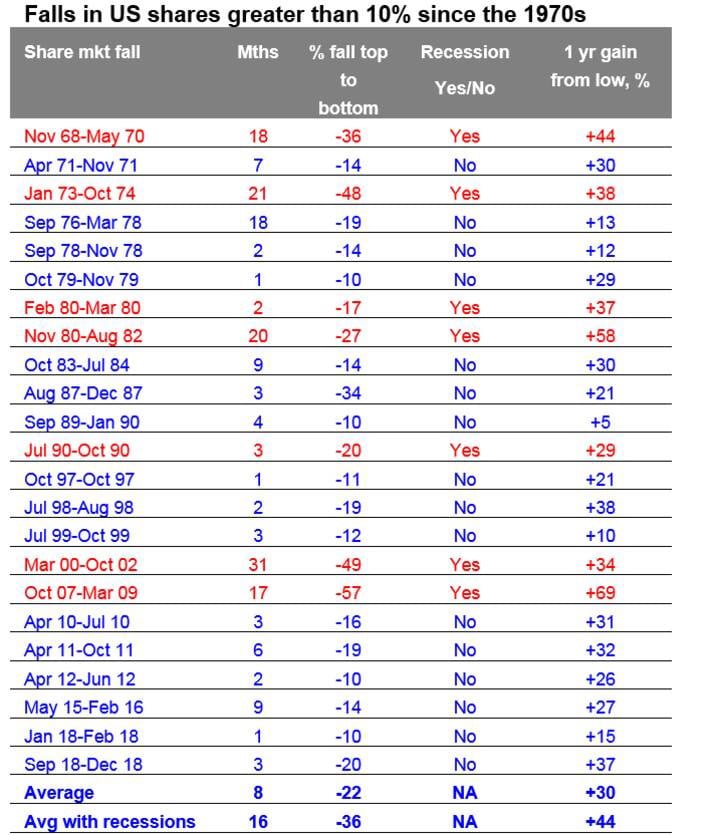

Secondly, the main driver of experiencing a correction (or a mild bear market with a potential 20% decline that turns around relatively quickly, like we saw in 2015-16) or a major bear market (like the GFC in 2008-09) is whether we see a recession or not, particularly in the US, which is where they tend to lead from.

The next table shows US share market falls greater than 10% since the 1970s. The first column shows the period of the fall, the second shows the decline in months, the third the percentage decline from top to bottom, the fourth whether the decline was associated with a recession or not, and the fifth shows the gains in the share market one year after the low. Falls associated with recessions are highlighted in red.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital.

Several points stand out:

- First, share market falls associated with recession tend to be longer and deeper.

- Second, after the low the share markets generally rebound sharply – which invariably makes it very hard for investors to accurately time. By the time they realise what has happened and get back in the market, it is above where they sold.

- Finally, as would be expected, the share market rebound in the year after the low is much greater, following falls associated with recession.

So, whether a recession is imminent or not in the US is critical, in terms of whether we will see a major bear market or not. In fact, the same applies to Australian shares. Our assessment is that a US/global recession is not inevitable. We have not seen the excesses – overall debt growth (although housing debt is a source of risk in Australia), over-investment, capacity constraints and inflation – that normally precede recessions in the US, globally or Australia. And we have not seen the sort of monetary tightening that leads into recession. In fact, monetary conditions remain very easy. However, the uncertainty around the coronavirus outbreak, and the likelihood of economic shutdowns designed to contain it beyond those in China, do suggest a greater than normal risk on this front. That said, even if there were a recession, growth would likely rebound quickly once the virus came under control as economic activity sprang back to normal, helped by policy stimulus.

Another consideration is that selling shares or switching to more conservative options after a correction or major fall will realise a capital loss. With the talk of billions being wiped off the share market one might be tempted to sell. But this will turn the paper loss into a real loss with no hope of recovering.

In fact, having some cash available to purchase cheaper assets is the better strategy over the long term. So, the key is wait for opportunities then use cash wisely to invest into quality assets when prices are cheaper. It’s impossible to time the bottom and one way to do it is to average it over time.

Lastly, while shares have fallen dividends from the market have not. They will come under pressure as the economy and profits take a hit from a longer and deeper coronavirus outbreak, but companies like to smooth their dividends over time. Post the GFC we saw income in most cases return to normalised levels after 12 months. Further, the income you receive from Australian shares is likely to remain attractive, particularly when compared to bank deposits.

In times like this negative news can take over. Turn down the noise. We are told about billions being wiped off share markets and warnings off disaster, but not so much about market rebounds and the rising long-term trend of share prices. The news media does not offer perspective or solution. We suggest sticking to your long-term investment plan, based on quality, income and capital growth and taking advantage of share market corrections where possible.

If you would like a review of your situation or know someone that might benefit from an advice relationship, please contact us.

The information contained in this article is of a general nature and does not take into account personal circumstances. Before making any decisions based on the factual information contained in this document please consult with your financial adviser.